Louanne Learning

Active Member

Member

New Member

Role Play Moderator

The brain then processes all this and forms opinions on the world.

Ah, and herein lies the mystery

The brain then processes all this and forms opinions on the world.

Dare I suggest Niccolo Machiavelli?I have read The Prince, and although Machiavelli's work has been derided as immoral, dangerous and controversial, he actually makes some very interesting points - for instance, on self-control:

Machiavelli emphasizes self-control not as emotional denial, but as a strategic tool for a leader to maintain power. He views emotional outbursts as weaknesses that can be exploited, so a prince must cultivate emotional discipline, appearing outwardly merciful, faithful, humane, honest, and religious while strategically acting as a lion (for strength) and a fox (for cunning) to adapt to circumstances and avoid being manipulated.

It advises rulers to prioritize political necessity and power over traditional morality, arguing that a leader must be willing to use unethical and even cruel means to maintain control. The book controversially separates politics from ethics, advocating for deception, treachery, and violence when deemed necessary for the state.

This led to it being seen as a handbook for tyrants, which made it was controversial at the time and still does today. But let me ask you four pertinent questions:

1. If The Prince had not been controversial, would it be memorable enough to last all this time?

2. Italy in Machiavelli's time was deeply divided, not only into regions like Tuscany vs. Calabria, but also into city-states ruled by warlords that constantly warred with each other, and made and broke alliances at the slightest whim. Doesn't that make these warlords into tyrants?

3. Can we, without being unfairly prejudicial, judge Machiavelli's work (or anyone else's work) by the standards of our own time? If so, doesn't that make us hypocrites?

4. Although many things have changed since The Prince was written, I'd say that many of Machiavelli's lessons -- a ruler's primary goal is to acquire and maintain power; leaders should be willing to use fraud, treachery, and violence; act based on how the world truly is, rather than how they wish it to be, etc. -- are still relevant today. Do you agree?

I used that theory to recover from a nervous breakdown caused by the disintegration of my first marriage, which coincided with the disintegration of the marriage of some of my best friends. I cobbled it together from some of the stuff I'd been reading by Ouspenski and Gurdjieff. When I talked to my friends about my "psychic destruction," they were very concerned that I was going nuts. Well, I was, but that's another story."... only morons fail to realise that it is only when you are broken that you can pick up the shattered fragments of you, to build the person you want to be."

In elementary school - I was I think in about grade 2 (about 7 years old) - the teacher drew a large oval shape on the blackboard. "This is your soul," she said. (Yes, I went to a Catholic school.)

Then she used the chalk to make some blotches on the soul. "This is sin on your soul," she said.

Then she used the blackboard eraser to wipe the sins off. "This is what happens when you are forgiven for your sins," she said.

Often, I feel like I do have a soul, especially in my connection with my husband who died. I still feel very connected to him. Clearly, physically, I am not. But what part of me feels so strongly that he is still with me?

But, faith is not merely a word that can be defined. It is also a concept. A concept is something different from a definition.

Faith as a concept covers a much broader scope - it encompasses things like trust, confidence, and hope.

May I direct your attention to Stephen Jay Gould's book Rocks of Ages.Got me thinking about the concept of certainty in not only philosophy, but science, too, and the relationship of certainty to the likelihood of acting on what you believe, or what you know.

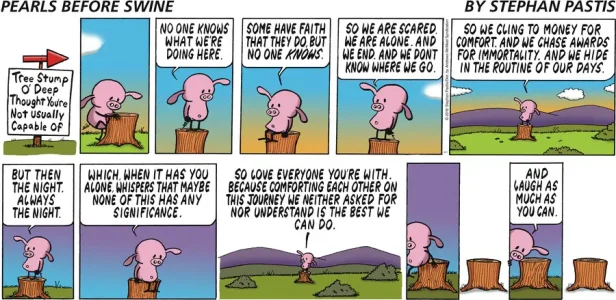

Why are we here?

I used that theory to recover from a nervous breakdown caused by the disintegration of my first marriage, which coincided with the disintegration of the marriage of some of my best friends. I cobbled it together from some of the stuff I'd been reading by Ouspenski and Gurdjieff. When I talked to my friends about my "psychic destruction," they were very concerned that I was going nuts. Well, I was, but that's another story.

But the parable I read concerned nails being driven into a wall. Those were the sins. The pulling out of the nails represented absolution. But the spackling of the wall to conceal the holes was penance.

Because he is now part of you, just as my first wife is part of me,

she was an agnostic. That is the only philosophically tenable view to take, she said, because science can neither design an experiment that proves that God exists nor design an experiment that proves that God did not exist. That made sense to me. I myself am a Bokononist, since I believe that "organized" religion is mostly a collection of comforting lies.

But it can be taken too far if faith prohibits skepticism. I quote Kurt Vonnegut: "Say what you will about the sweet miracle of unquestioning faith, I consider a capacity for it terrifying and absolutely vile."

It argues that science and faith are compatible when seen as two aspects or "magisteria" (now there's a Catholic word for you), which address two views of the human condition, one describing morality and one describing the natural world.

“We're here to get each other through this thing, whatever it is.”

With the question of Truth we find Nietzsche quite as ready to uphold his thesis as with all other questions. He frankly declares that "the criterion of truth lies in the enhancement of the feeling of power" …

Nietzsche proceeds to argue that what provokes the strongest sentiments in ourselves is also true to us, and, from the standpoint of thought, "that which gives thought the greatest sensation of strength"…

The provocation of intense emotion, and therefore the provocation of that state in which the body is above the normal in power, thus becomes the index to truth…

We had the whole pathos of mankind against us,—our notion of what "truth" ought to be, of what the service of truth ought to be…

Especially since he wasn't writing in English. Think of all the nuances for the synonyms for "power"...strength, force, influence and so on... and you have to wonder why the translator chose that particular word. "Kraft" in German can mean any of those things (and I'm guessing that "Kraft" was the word Nietzsche used).I suppose “power” is another one of those words – like “reality” and “truth” - open to various interpretations.

How are you defining truth? I feel like this is another one of those philosophy things where undefinable theories are built on undefinable elements and add up to an academic circle jerk.What ought the service of truth be?

I'm not sure why, but I have always had a little bit of an aversion to calling people "broken." I don't think we are ever broken, but rather, there are parts of us yet that we still need to discover. And those parts will bring us to a better place.

The answer: we are the ones who drive the nails in for our sins. Those are the only things we have to confess, in this analogy. Of course, sometimes events come from outside that damage our wall, but we aren't responsible for those.Ouch. The question that comes to my mind is - who was driving the nails into your soul?

I hear you.It really feels that way. But, at the same time, it really feels like a literal piece of me is missing. It's so hard to describe. He's here, but he's not here. My body was changed by his death.

One of my favorite quotes from the New Testament. As a woodworker, I can relate to that. Some wood is good for building or for crafting or producing tasty food, while other wood is basically just good for firewood.I came across a quote of Jesus' today, and thought it was pretty cool. Jesus said, “You will know them by their fruits.” (Matthew 7:16)

But, our morality comes out of the natural world. My morality came out of my evolution as a social animal. Morality is embedded in our biology. As social animals, the more we contributed to the group, the more we belonged to the group, the more we built meaningful relationships, the greater was the survival of the group.

The scientific theory used to support this truism of who we are - the Theory of Inclusive Fitness – states that an organism’s genetic success is believed to be derived from cooperation and altruistic behavior.

True dat. If you can't agree on the definitions, there's no point in building on them, unless you're a PhD candidate in a philosophy or theology course. Then you could probably churn out a thesis on some point or other.How are you defining truth? I feel like this is another one of those philosophy things where undefinable theories are built on undefinable elements and add up to an academic circle jerk.

I'd rather get a root canal through my assPhD candidate in a philosophy

Especially since he wasn't writing in English. Think of all the nuances for the synonyms for "power"...strength, force, influence and so on... and you have to wonder why the translator chose that particular word. "Kraft" in German can mean any of those things (and I'm guessing that "Kraft" was the word Nietzsche used).

How are you defining truth? I feel like this is another one of those philosophy things where undefinable theories are built on undefinable elements and add up to an academic circle jerk.

Just because we're "broken" doesn't mean that we can't be glued back together, sometimes with higher-quality pieces that weren't available before. The seams will probably show, though. I've heard that scars are just tattoos with more interesting stories to tell.

The answer: we are the ones who drive the nails in for our sins.

So it is with people, which is why you have to cut other people a little slack from time to time.

The trouble with the phrase "survival of the fittest" is that it's usually taken to mean the survival of the strongest or the most dominant. But I think it would be better phrased as "survival of the best fit"...the ones that survive are the ones that best fit the ecological niche that's there to be exploited, and cooperation is a most useful tool for that.

Well, this isn't what I had in mind when I posted - that the ruler should put his own interests above those of the citizens.

In fact, when the maintenance of power becomes the main goal, the common people generally suffer for it.

The Prince may be a piece of political philosophy, but I was thinking more of the philosophy that steers leaders to the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

Or as that old sage Mark Twain put it, "Man is a Religious Animal. He is the only Religious Animal. He is the only animal that has the True Religion---several of them."If you think your truth is the ultimate, objective truth, you 're more likely to impose it on others.